When the U.S. Government Defaulted On Its Debts

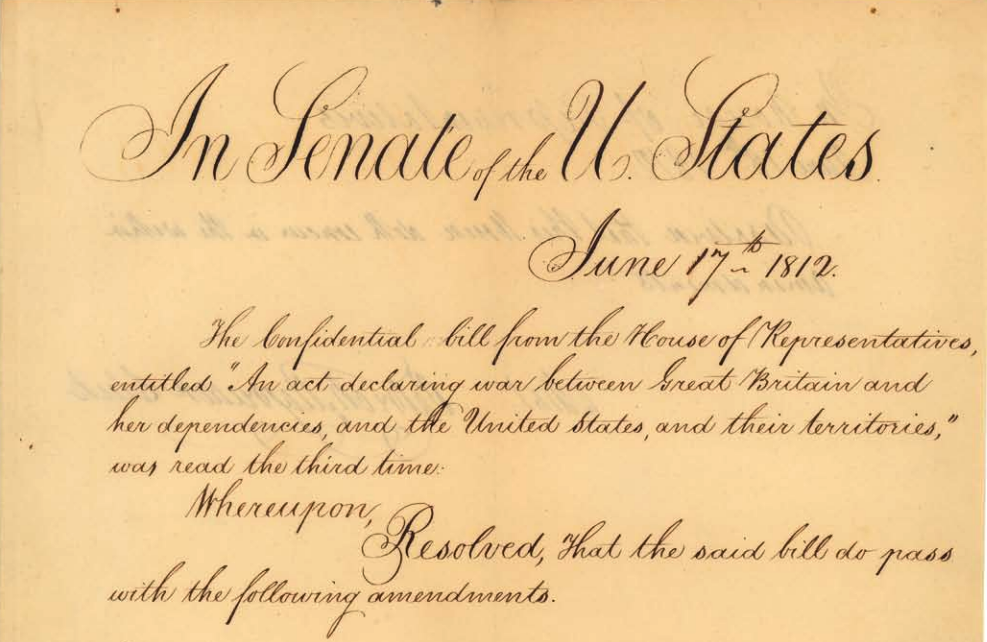

On June 17, 1812, the U.S. Senate resolved to declare war on the British Empire. Document Courtesy of the National Archives.

On June 17th, the U.S. Senate voted to approve the resolution declaring war on the British Empire by a 19 to 13 margin.

You can view the Senate’s approval of the resolution declaring war on the British Empire here.

The House of Representatives had already voted to approve war against the British Empire by a margin of 79 to 49.

President Madison signed the bill into law on June 18, 1812, marking the start of the War of 1812.

This declaration of war was the first in American history.

(To learn more about the legal mechanisms by which the U.S. government declares war, see here).

The War of 1812 proved ruinous to American finances: just over two decades after Alexander Hamilton implemented his plan to get the newly established nation’s fiscal situation in order, a series of Democratic-Republican fiscal policies and the war had wrecked them.

First, an 1802 internal tax repeal under President Thomas Jefferson left the federal government entirely dependent on customs, tariffs, and the sale of public lands for its revenues; revenues which were bound to fall as war took a toll on American trade.

Treasury Secretary Albert Gallatin appealed for the reinstatement of an internal tax in January of 1811, but Congress rebuffed his proposal.

To make matters worse, the United States entered the war – a period that naturally required increased federal expenditures and therefore a greater need to issue debt – without a fiscal agent to collect the government’s revenues and help it issue debt.

The role had previously been filled by the Bank of the United States, the brainchild of Alexander Hamilton inspired by the Bank of England.

But in 1811, just prior to America’s declaration of war against Britain in 1812, the Jeffersonian-majority Congress allowed the Bank’s charter to expire un-renewed.

In addition to the absence of a fiscal agent, the U.S. government also suffered from a lack of control over monetary policy.

Today the Federal Reserve Bank controls U.S. monetary policy and could take steps to prevent a default by the federal government should the treasury run into trouble.

But during this early period of American history, the country didn’t even operate with a single unified national currency, let alone a coherent monetary policy: America’s monetary system was a mess.

Carpenters Hall: 1791- 1797 Headquarters of the Bank of the United States in Philadelphia.

1797-1811 Headquarters of the Bank of the United States, Philadelphia.

So the United States would enter war with a global empire lacking sufficient tax revenues to fund the conflict and absent strong institutions capable of managing the nation’s finances at a time when they would naturally come under increased strain: it was only a matter of time before the federal government ran out of money.

In the summer of 1813, with America already mired in conflict for a year, Congress belatedly took steps to lay internal taxes.

But it was too late: the U.S. government’s borrowing rates had already spiked as lender confidence deteriorated and would continue rising toward prohibitive levels even after the new taxes were legislated.

And in 1814, with the Treasury’s coffers running empty, the U.S. government defaulted on some of its debts (contrary to the long-standing myth repeated by many of today’s media and politicians that America has never defaulted on its obligations).

America’s fiscal difficulties would prompt Treasury Secretary Alexander Dallas to write in a November 1814 letter that the “treasury was suffering from every kind of embarrassment.”

In a subsequent December 2, 1814 letter, Dallas detailed overdue interest payments on Treasury Notes held by lenders in Philadelphia, New York, and Boston.

The War of 1812 was concluded with the Treaty of Ghent (agreed in Ghent, located in present-day Belgium) in 1814.

The Treaty required that all territories captured during the war be returned.

Formal title of the Treaty of Ghent. Document Courtesy of the National Archives.

The fiscal difficulties America experienced during the war led many policy-makers to conclude that having a central bank-like institution that could serve as a fiscal agent and shape monetary policy would be helpful during war.

At the same time, several wealthy businessmen, worried that unmanaged inflation was eroding their profits, carried out an aggressive campaign to convince Congress to charter a new national bank.

The fiscal debacle during the war and pressure from these business and banking elites prompted a sharp about-face in Washington.

President Madison – a Jeffersonian Republican – decided to support the chartering of a new central bank-esque institution in 1816, a mere 5 years after Jeffersonian Republicans had allowed the charter of Bank of the United States to expire un-renewed.

The new institution would be known as the Second Bank of the United States.

Written By: Aiden Singh Published: July 28, 2020 Sources