Wishful Thinking On UK Inflation

By Simon Wren-Lewis, June 26, 2023

Simon Wren-Lewis is Emeritus Professor of Economics and Fellow of Merton College, University of Oxford.

I have been surprised by the extent and persistence of UK inflation over the last few months, along with many others. So what did I get wrong?

Why is UK inflation so persistent?

Let’s start by looking for clues. The biggest is that inflation is proving more of a problem in the UK than elsewhere. Here are a couple of charts from Newsnight’s Ben Chu. The UK has the worst headline inflation in the G7 and the worst core inflation (excluding energy).

That Brexit would make inflation worse in the UK than other countries is not a surprise. I talked about this over a year ago, although back then US core inflation was higher than in the UK. In that post I listed various reasons why Brexit could raise UK inflation (see also here). Could some of those also account for its persistence?

The one most commonly cited is labour shortages brought about by ending free movement. Here is the latest breakdown of earnings inflation by broad industry category.

Around the middle of last year the labour scarcity story was clear in the data. One key area where there was a chronic shortage of labour was in hotels and restaurants, and wage growth in that sector was leading the way. However if we look at the most recent data, that is no longer the case, and it is finance and business services where earnings growth is strongest. This dovetails with a fall in vacancies in the wholesale,retail, hotels and restaurant sectors since the summer of last year (although the level of vacancies remains above end-2019 levels). Has there been a recent increase in vacancies in finance and business services? No, the explanation for high earnings growth in that sector lies elsewhere.

Before coming to that, it is worth noting that any earnings growth numbers above 3-4% are inconsistent with the Bank’s inflation target, and the labour market does remain tight, although not as tight as a year ago. One partial explanation for UK inflation persistence is that it reflects the consequences of persistently high (in excess of 3-4%) wage inflation, which in turn reflects a tight labour market.

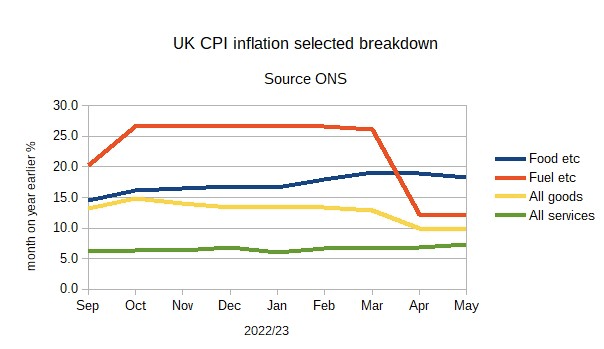

UK price inflation is no longer just a consequence of high energy and food prices, as this breakdown makes clear.

While energy and food prices are still higher than average inflation, the most worrying line from the Bank's point of view is the green one for inflation in all services. It is this category where inflation is (slowly) increasing, and the latest rate of 7.4% is the main reason why UK inflation appears to be so persistent. It is no longer the case that UK inflation is being generated by external factors that cannot be influenced by the Bank of England. That is also why it can be a bit misleading to talk about inflation persistence or sticky inflation, because the prices that are going up now are not the same as were going up just a year ago.

This high level of services inflation could be a response to high nominal earnings growth, with perhaps still some lagged effect from higher energy costs [1], but recent data for profits suggests a third factor involved. Here is the share of the operating surplus for corporations (i.e. corporate profits) to GDP since 1997.

Graph: UK Profit Share.

Apart from a spike in the first quarter of the pandemic, this measure of the profit share has stayed below 24% since 2000, averaging about 22% between 2000 and 2022. However the end of 2022 saw this share rise to 22.5%, and the first quarter of this year saw a massive increase to 24.7%. We have to be careful here, as this sudden increase in the profit share could be revised away as better data becomes available. But if it is not, then it looks as if some of the recent persistence is coming from firms increasing their profit margins.

Why might firms be increasing their profit margins? This might not be unexpected during a period where consumer demand was very buoyant, but with the cost of living crisis that isn’t happening. It may be that firms have decided that an inflationary environment gives them cover to raise profit margins, something that seems to have happened in the US and EU. However another factor is Brexit once again. EU firms now face higher costs in exporting to the UK, and this may either lead them to withdraw from the UK market altogether, or to try and recover these costs through higher prices. Either way that allows UK firms competing with EU firms in the UK market to raise their prices. If you look at what I wrote a year ago, that effect is there too, but it was impossible to know how large it would be.

What is to be done?

The mainstream consensus answer is to use interest rates to keep demand subdued to ensure wage and domestically generated price inflation start coming down. It doesn’t matter if the inflation is coming from earnings or profits, because the cure is the same. Reducing the demand for labour should discourage high nominal wage increases, and reducing the demand for goods should discourage firms from raising profit margins. In this context, the debate about whether workers or firms are responsible for current inflation is beside the point.

That does not necessarily imply the Monetary Policy Committee of the Bank was right to raise interest rates to 5% last week. Indeed two academic economists on the MPC (Swati Dhingra and Silvana Tenreyro) took a minority view that rates should stay at 4.5%. I probably would have taken that minority view myself if I had been on the committee. The key issue is how much of the impact of previous increases has yet to come through. As I note below, the current structure of mortgages is one reason why that impact may take some time to completely emerge.

That demand has to be reduced to bring inflation down is the consensus view, and it is also in my opinion the correct view. There is always a question of whether fiscal policy should be doing some of that work alongside higher interest rates, but it already is, with taxes rising and spending cuts planned for the future. Increasing taxes further on the wealthy is a good idea, but it doesn’t help much with inflation, because a large proportion of high incomes are saved. An argument I don’t buy is that higher interest rates are ineffective at reducing demand and therefore inflation. The evidence from the past clearly shows it is effective.

For anyone who says we should discount the evidence from the past on how higher interest rates reduce demand because the world is different today, just think about mortgages. Because of higher house prices, the income loss of a 1% rise in interest rates is greater now than it was in the 70s or 80s. Yet because many more people are on temporarily fixed rate mortgages, the lag before that income effect is felt is much greater, which is an important argument for waiting to see what the impact of higher rates will be before raising them further (see above). There is however one area where the government can intervene to improve the speed at which higher interest rates reduce inflation, which I will talk about below.

With the economy still struggling to regain levels of GDP per capita seen before the pandemic [2], it is quite natural to dislike the idea that policy should be helping to reduce it further. This unfortunately leads to a lot of wishful thinking, on both the left and the right. For some on the left the answer is price controls. The major problem with price controls is that they tackle the symptom rather than the cause, so as soon as controls end you get the inflation that was being repressed. In addition they interfere with relative price movements. They are not a long term solution to inflation.

Sunak at the beginning of the year made a deceitful and now foolish pledge to half inflation. It was deceitful because it is the Bank’s job to control inflation, not his, so he was trying to take the credit for someone else’s actions. It has become foolish because there is a good chance his pledge will not be met, and there is little he can do about it. When challenged about making pledges about things that have little to do with him he talks about public sector pay, but this has nothing to do with current inflation (see postscrit to this)! As I noted last week, the Johnsonian habit of lying or talking nonsense in public lives on under Sunak.

The idea among Conservative MPs that mortgage holders should somehow be compensated by the government for the impact of higher interest rates is also wishful thinking on their part, reflecting the prospect of these MPs losing their seats. While there is every reason to ensure lenders do everything they can for borrowers who get into serious difficulties, to nullify the income effect of higher mortgage rates would be to invite the Bank to raise rates still further. [3] Sunak cannot both support the Bank in getting inflation down and at the same time try and undo their means of doing so. In addition there are other groups who are in more need of protection from the impact of inflation than mortgage holders.

Another argument against high interest rates is that inflation today reflects weak supply rather than buoyant demand, so we should try to strengthen supply rather than reduce demand. Again this looks like wishful thinking. First, demand in the labour market is quite strong, and there are no clear signs of above normal excess capacity in the goods market. Second, the problems we have with supply - principally Brexit - are not going to be fixed quickly. To repeat, it is the domestically generated inflation rather than the external price pressures on energy and food that represent the current problem for inflation.

A similar argument relates to real wages. People ask how can nominal wage increases be a problem, when real wages are falling and are around the same level as they were in 2008? Part of the answer is that, as long as the prices of energy and food remain high, real wages need to be lower. (The idea that profits alone should take the hit from higher energy and food prices is ideological rather than sound economics.) Because higher energy and food prices reduce rather than increase the profits of most firms, they are bound to pass on higher nominal wages as higher prices.

Yet there is one new policy measure that would help just a little with the fight against inflation, and so help moderate how high interest rates need to go. As I noted earlier, the sector leading wage increases at the moment is finance and business services. In finance at least, some of this will be profits led because of bonuses or implicit profit sharing. Bank profits are rising for various reasons, one of which is that the Bank of England is paying them more for the Bank Reserves they hold. There is a sound economic case for taxing these profits whatever is happening to inflation, and the fact that higher taxes on banks could help reduce inflationary pressure is a bonus right now.

What did I get wrong? Just how bad the state of the UK economy has become.

While the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) of the Bank of England may have underestimated the persistence of UK inflation, I have for some time been arguing that the Bank has been too hawkish. On that, MPC members have been proved right and I have been wrong, so it is important for me to work out why.

A good part of that has been to underestimate how resilient the UK economy has so far been to the combination of higher interest rates and the cost of living crisis. I thought there was a good chance the UK would be in recession right now, and that as a result inflation would be falling much more rapidly than it is. It seems that many of those who built up savings during the pandemic have chosen (and been able) to cushion the impact of lower incomes on their spending.

But flat lining GDP, while better than a recession, is hardly anything to write home about. As I noted above, UK GDP per capita has yet to regain levels reached in 2018, let alone before the pandemic. If the UK economy really is ‘running too hot’ despite this relatively weak recovery from the pandemic, it would imply the relative performance of the UK economy since Brexit in particular (but starting from the Global Financial Crisis) was even worse than it appeared just over a year ago. If I am being really honest, I didn’t want to believe things had become that bad.

This links in with analysis by John Springford that suggests the cost of Brexit so far in terms of lost GDP may be a massive 5%, which is at the higher end (in not above) what economists were expecting at this stage. If in addition the UK economy is overheating more than other countries (which is a reasonable interpretation of the inflation numbers), this number is an underestimate! (UK GDP is flattered because it is unsustainable given persistent inflation.)

Of course this 5% or more number is really just our relative performance against selected other countries since 2016, and so it may capture other factors beside Brexit, such as bad policy during the pandemic, chronic underfunding of health services and heightened uncertainty due to political upheaval detering investment.

In thinking about the relative positions of aggregate demand and supply, I did not want to believe that UK supply had been hit so much and so quickly since 2016. [4] The evidence of persistent inflation suggests that belief was wishful thinking. It seems the economic consequences of this period of Conservative government for average living standards in the UK has been extraordinarily bad.

Footnotes

[1] The UK was also particularly badly hit by high energy prices.

[2] In the first quarter of this year GDP per capita is not only below 2019 levels, it is also below levels at the end of 2017!

[3] Higher interest rates do not reduce demand solely by reducing some people’s incomes. They also encourage firms and consumers to substitute future consumption for current consumption by saving more and spending less. However with nominal interest rates below inflation, real interest rates so far have been encouraging the opposite.

[4] I probably should have known better given what happened following 2010 austerity. While it is hard for politicians to significantly raise the rate of growth of aggregate supply, some seem to find it much easier to reduce it substantially.