It’s The Balance Sheet, Stupid!

By Dag Detter, March 25, 2025

Principle of Detter & Co., Financial Advisor to Governments Worldwide, & Former President of the Swedish National Wealth Fund.

He Can Be Booked For A Speaking Engagement Here.

Governments are, in effect, the most significant wealth managers in a country, even if they do not behave as one.

One reason they don’t act like a professional wealth manager is that they lack an understanding of their wealth. Despite being the largest and most complex organisations we have, governments typically do not hold themselves to the accounting standards they impose on others, nor do they use accounting information as a basis for decision-making, except possibly for New Zealand.

This is similar to using a map intended for travel in a horse-drawn carriage while driving a modern car at high speed: the information on the map was relevant when the roads were built long ago but may be entirely irrelevant for a contemporary traveller.

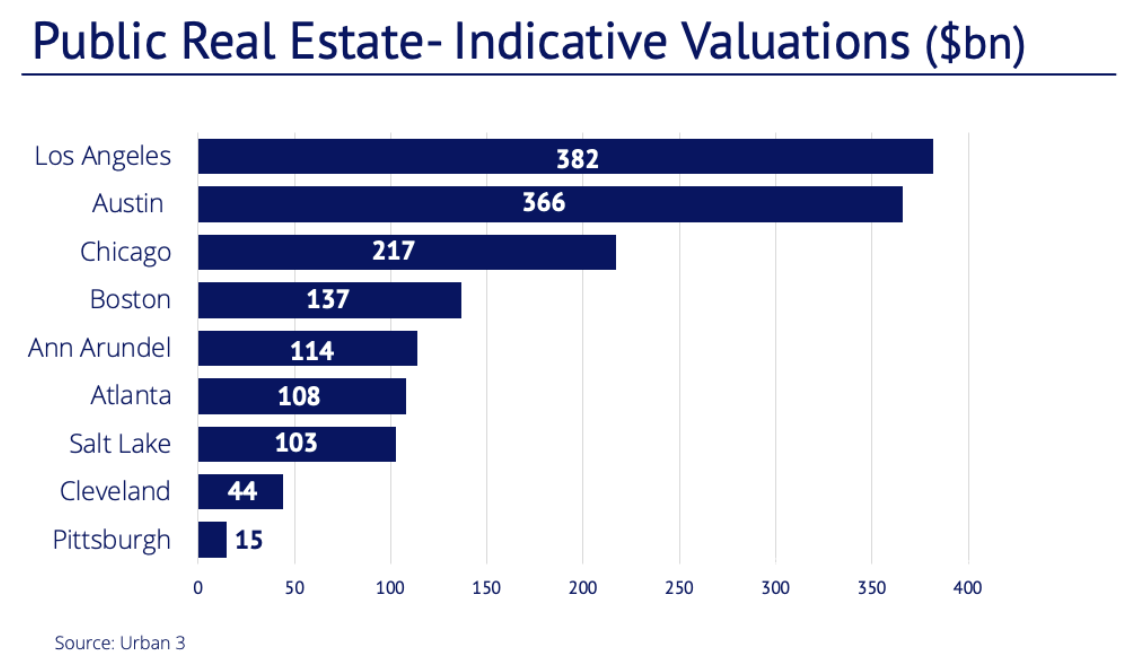

This issue is most prominent with government-owned real estate, as governments are by far the largest property owners in every city, county, and state. Their real estate portfolios are often worth half the total market value of property within their jurisdiction, roughly equivalent to the economic output of that area. Yet, they pay little attention to the value of their assets or to managing them effectively, in order to provide the best value to taxpayers.

For instance, upon assessing the value of its properties, the city of Pittsburgh discovered that they were worth 70 times the portfolio value recorded in the city’s financial statements. If managed effectively, these assets could generate additional non-tax government revenue that surpasses the current tax revenue produced by the city. And Pittsburgh is not alone in this regard: many cities do not evaluate and publish the fair market value of their real estate portfolios or operational assets. Consequently, they lack the information needed to unlock the revenue those assets could produce.

In the US, the value of public commercial assets exceeds 150 per cent of GDP, amounting to $45 trillion. Two-thirds of that value is comprised of real estate, while the remainder consists of operational assets such as water utilities, ports, airports, and subway systems. However, we cannot ascertain these values definitively because, unlike private-sector wealth managers, the US government does not produce audited financial statements that report their current value.

Failing to use proper accounting overlooks not only the asset, but also much of the liability side of the governments’ balance sheet. Non-debt liabilities, such as public sector pension obligations - which could be even larger than the government’s debt - are ignored. Without proper accounting, these liabilities will not be understood properly and subsequently will not be managed effectively.

For example, the Department of Defense, has made several attempts to value its trillion-dollar real estate portfolio but has never publicised the results or reported them in its financial statements. It has never been able to produce auditable financial statements as required by law.

Consequently, cash-strapped public bodies struggle to make the best decisions such as determining whether they can better fulfil their needs through better utilisation of existing assets or through selling them. This represents both a significant missed opportunity and a debilitating failure of imagination.

Just as a company or household examines its balance sheet to enhance its wealth, so should a government. Managing wealth is not rocket science; it is done daily in the private sector. According to IMF research, better management of government assets could generate non-tax revenues equivalent to 3 percent of GDP annually. This would mean an additional US$850 billion in non-tax revenues annually for the US.

An independent holding company - a public wealth fund (‘PWF’) at the local, regional or federal level - is key to exploiting this opportunity. Establishing PWFs facilitates better asset management and value extraction for taxpayers, thus eliminating the need for underpriced asset sales. A PWF is different from a sovereign wealth fund (SWF). Most existing SWFs are funded with budget surpluses driven by exceptionally high revenues, often from the extraction of natural resources. A PWF is established to manage existing or new public commercial assets—often property or infrastructure-related and government-owned enterprises—in a manner that maximises financial value for the taxpayer.

Managing its balance sheet through the use of a PWF has been a key component in Singapore’s transition from a developing country to a developed economy within one generation. Temasek, the Singaporean PWF managing the city’s operational assets, has expanded from an initial portfolio valued at US$0.3 billion to US$292 billion since its inception in 1974.

Despite lacking any natural resources or even the capacity to generate its electricity at the time of independence in the 1960s, it has built what is likely the largest sovereign portfolio in the world, divided between its PWF, Temasek, and its SWF, the GIC, and the Monetary Authority of Singapore. Singapore’s sovereign portfolio is estimated to have reached almost four times the country’s GDP and is larger than that of Norway and Saudi Arabia, which derive their wealth from abundant natural resources, while Singapore achieved its wealth through sheer hard work, ingenuity, and diligence.

Under Singaporean law, half of the net investment returns must be reinvested for future returns. About one-fifth of government spending is funded by the investment returns of these funds, contributing an average annual revenue stream of about 3.4% of GDP over the past 5 years, almost equal in size to Singapore’s corporate tax revenue.

If a government truly wishes to ensure its country’s prosperity, today's political slogan in the U.S. and elsewhere ought to be, “It’s the balance sheet, stupid!” That is where focus should lie, not because it is easy, but because it is where opportunity exists.

——————